Neither a politics of identity informed by theories of intersectionality nor reductive economistic readings of Marxism are adequate for a modern socialist project, argues Donald Parkinson.

Socialism is still primarily a subculture in the United States, and while we are seeing the rise of organizations such as the Democratic Socialist of America (DSA), within them various fissures and debates over the correct approach to socialist politics are emerging. One of the most prominent debates (not only in the DSA but throughout the entire US left) is between perspectives that can be separated into two main camps: identity politics and “class-first” economism. With identity politics, there is a focus on extra-economic issues of oppression as a means to mobilize activists around specific identity groups and those who stand as allies to these groups, theoretically basing itself on the concept of intersectionality. “Identity politics” is often used as a derisive adjective for these forms of activism, and it is often hard to differentiate between the politics of civil rights and identity politics as separate categories. At times it is difficult to tell which critiques of identity politics are simply echoing right-wing talking points and which are actually pursuing an agenda of socialism and human liberation, a fact that is often used to dismiss all attacks on identity politics. One in-vogue reaction to the rise of identity politics is a sort of social-democratic economism that aims to focus on building the broadest political coalition possible around basic economic issues while avoiding any political issues that might be seen as divisive. My aim here is to argue that both approaches are dead ends.

Writers critiqued as examples of identity politics include Ta-Nehisi Coates, bell hooks and Kimberlé Crenshaw. For this article, we shall focus on Crenshaw, who mapped out the theory of intersectionality in her articles “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics” and “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” In “Demarginalizing,” Crenshaw focuses on the experience of Black women and the unique form of oppression they face as something which cannot be understood purely through the axis of gender or race. She offers the example of the DeGraffenreid v General Motors case where five Black women sued General Motors for discrimination against Black women, citing that the firm had not hired any Black women from the years 1964 and 1970 and afterwards had disproportionately laid off Black women due to the seniority system. Crenshaw points out how these attempts to sue GM were countered through pointing out how they had hired women, albeit white women, as well as pointing to an earlier lawsuit against racial discrimination that related to Black men. While it could be shown that GM did not discriminate simply based on gender or race, Crenshaw argued that it did discriminate against the particular identity of Black women. Hence, it was not enough to simply use the categories of race or gender; one had to understand how these oppressions intersected in particular ways. To quote Crenshaw,

“The court’s refusal in DeGraffenreid to acknowledge that Black women encounter combined race and sex discrimination implies that the boundaries of sex and race discrimination doctrine are defined respectively by white women’s and Black men’s experiences. Under this view, Black women are protected only to the extent that their experiences coincide with those of either of the two groups.”1

Crenshaw concludes that Black women’s oppression cannot be understood as either gender- or race-based but as an intersection of these two axes. She refers to this as double discrimination, similar to discrimination faced by Black men or white women but nonetheless unique and irreducible to either. To use either category of race or gender on their own can only obscure the actual discrimination faced. To further investigate this issue, Crenshaw explores the life experiences of Sojourner Truth and how they challenged not only conventional notions of womanhood but also notions of Black women as less than women. In this context, Sojourner Truth’s experience facing both racial and gender oppression indicates the inability of most manifestations of feminism to speak to the experiences of Black women, and by default only speaking to the experiences of white women. When feminism discusses the issues of women, according to Crenshaw, the unspoken assumption is that the subject of discussion is white women. Black women, facing a unique status of oppression, are therefore left out of the picture.2

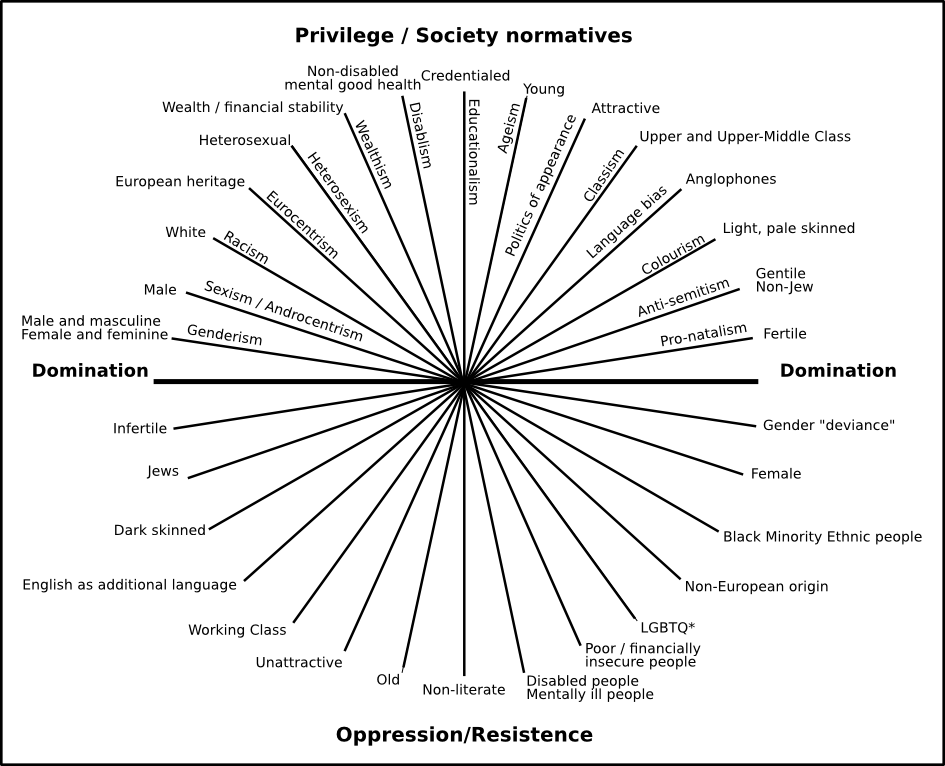

At first glance, there is little that is outright objectionable in Crenshaw’s claims. Black women clearly suffer from a form of double oppression. Crenshaw is able to successfully show how these intersecting forms of oppression not only exist but are masked by the legal system. Yet, what her argument misses, as Mike Macnair points out, is the element of class analysis. The DeGraffenreid v General Motors case, for example, is just as much an expression of class power embedded in bourgeois law as it is an expression of the inability of the law to adequately address the experiences of overlapping oppressions. What Crenshaw doesn’t mention is that these lawsuits were an expression of capitalist firms using the law to keep labor as a pliable resource to be hired and fired at will.3 This cannot be understood simply in terms of discrimination, but as an element of structural exploitation due to the class relations that govern capitalist production. When intersectional analysis does address class, it tends to only address class in terms of discriminations against individuals based on class background, known as “classism.”

An additional weakness of intersectionality is its merely descriptive, rather than explanatory, function. It demonstrates that individuals experience oppression in multiple ways that overlap, but it doesn’t explain how these oppressions are reproduced in society. The Marxist analysis of racism and patriarchy aims to understand how these oppressions are linked to social reproduction and therefore can be abolished by changing society. Intersectionality, because of its genesis in legal theory, seeks to describe the experience of various oppressions and end the practice of these oppressions within the framework of bourgeois law and order. The result is that the primary goal of the activist practice associated with intersectionality, commonly known as social justice, is making existing social relations fairer (or just) to the oppressed as opposed to changing the foundations of society. Because it is not informed by a critique of the way oppressions are reproduced in the division of labor and class relations of society, it tries to make changes to the legal practices or social customs of society. While legal practices and social customs are certainly material and structural, and many of the proposed changes to them are desirable, it is necessary that we situate fights for such reforms within a greater framework and strategy of revolutionary change in order to challenge not just certain unfair aspects of society, but the underlying basis of our fundamentally oppressive society as a whole.

The political practice associated with intersectionality tends to take the form of single-issue activism and coalitions as well as individual forms of consciousness-raising (such as privilege checking, call-outs, etc). Emphasis on the particular forms of oppressions that specific groups experience can cause a belief that only members of the specific oppressed group in question can lead activist campaigns. This creates a fragmented politics wherein certain extreme cases only the “in-group” can speak on a certain issue while the “out-group” can only listen and aid their struggles as “allies.” This aspect of identity politics or “woke-ism” is the most important aspect to critique, as in practice it tends toward a breakdown of solidarity and takes a project for universal human emancipation off the table.

It should be noted than Crenshaw states that “intersectionality is not being offered here as some new, totalizing theory of identity” and that she does not “mean to suggest that violence against women of color can be explained only through the specific frameworks of race and gender considered here.”4 She also adds that issues of class and sexuality are of great importance despite not being mentioned explicitly. However, regardless of how Crenshaw intended for her theory to be used, it has undoubtedly become an item of faith consistently invoked on the left. To understand the debates within the left over identity politics, one cannot ignore the work of Crenshaw. It should be added that Crenshaw was not the first theorist to discuss the unique oppression of Black women. Theorists such as Angela Davis and Claudia Jones also discussed the ways in which race, class, and gender interacted, but within a specifically Marxist framework. When addressing intersectionality we mean the specific theories developed by Crenshaw, not an analysis that involves the categories of race and gender as well as class. One could even argue that intersectionality is an essentially liberal co-option of Marxist critiques of oppression that have existed within the socialist movement for quite some time.

There is no shortage of left critiques of intersectional theory and identity politics. “Exiting the Vampire Castle” by Mark Fisher is a famous example. It is a description and critique of the cruel and anti-solidaristic behavior that is associated with “woke-ism”, where individuals police each other’s language in often arbitrary ways and the atmosphere is marked by a “stench of bad conscience and witch-hunting moralism.”5 “Exiting the Vampire Castle” was received with no shortage of vitriol as it was seen as echoing conservative talking points and attacking the left in a way that focused on its excesses and exaggerated them. Others found that Fisher’s analysis resonated with their negative experiences in the left. Regardless of what one thinks of Fisher’s arguments, it was symptomatic of a greater sense of dissatisfaction in the left with identity politics that would lead to its own counter-movement.

A primary theorist of this counter-movement is Adolph Reed Jr. While Reed has been writing since the 1970s, his critique of cultural politics (specifically Black politics) came to relevance as many leftists tried to construct a negation of the “woke” left. Others, such as Adam Proctor of the podcast Dead Pundits Society and Angela Nagle, the author of the book Kill All Normies, would follow in his footsteps. Some of their opponents argue that these writers form a tendency known as the “class-first left”, and closely associate them with the “dirtbag left”. Reed is the most intelligent and worthwhile of these personalities so we will primarily look at his work. He is most famous for his interpretation of identity politics as a form of neoliberal class politics representing a faction of the petty-bourgeoisie. He summarizes his assessment in this way:

“[Identity] politics is not an alternative to class politics; it is a class politics, the politics of the left-wing of neoliberalism. It is the expression and active agency of a political order and moral economy in which capitalist market forces are treated as unassailable nature.

An integral element of that moral economy is displacement of the critique of the invidious outcomes produced by capitalist class power onto equally naturalized categories of ascriptive identity that sort us into groups supposedly defined by what we essentially are rather than what we do. As I have argued, following Walter Michaels and others, within that moral economy a society in which 1% of the population controlled 90% of the resources could be just, provided that roughly 12% of the 1% were black, 12% were Latino, 50% were women, and whatever the appropriate proportions were LGBT people.

It would be tough to imagine a normative ideal that expresses more unambiguously the social position of people who consider themselves candidates for inclusion in, or at least significant staff positions in service to, the ruling class.”6

Reed has developed this thesis in his political commentary since the 1970s, and there is much of merit in his work. His critique of a politics that moves away from economics and definite material goals to an exclusive focus on changing culture is certainly valid when we consider the utter disconnect of the left from the workers’ movement and its inability to win real victories beyond the symbolic. Much of Reed’s work focuses on issues of the politics of Black Americans, which he sees as constantly running into dead ends due to its emphasis on organizing identity-based coalitions around issues of anti-racism. Anti-racism, he argues, has become a form of politics to shore up the legitimacy of specific Black elite strata that developed in the aftermath of the Civil Rights movement, harkening back to this movement and its tactics despite their irrelevance for the current circumstances we live in.7

One of Reed’s specific targets is the demand for reparations. I do not aim to repeat the debate over reparations and its role in a political program here; what is more important is the general logic of Reed’s argument. While pointing out problems such as the difficulty of determining exactly who would get reparations, Reed’s primary point is that it is simply not politically feasible. To fight for reparations one would have to form a majority constituency and since Black Americans don’t form such a majority in America there is no viable way to do this. He argues for an alternative — something like the New Deal, a broad-based movement that fights for “access to quality health care, the right to a decent and dignified livelihood, affordable housing, quality education for all…pursued effectively only by struggling to unite a wide section of the American population that is denied those essential social benefits or lives in fear of losing them.”8

At the core of this argument is a claim that politics must steer clear of divisive political issues and instead focus on basic bread-and-butter economic issues to build a constituency. If we follow this logic then it no longer makes sense to fight for socialism as it is too divisive. Rather, it implies, we must focus on simple reformist campaigns to expand the welfare state. Reed has explicitly made this argument. At the April 2015 Platypus International Convention, Reed admitted that he desires socialism, but argued that a “new Popular Front” that “takes baby steps” to “decommodify public services” while avoiding the issue of socialism is what the moment calls for, and only after this has raised consciousness can socialism be brought up.9

What Reed is arguing for is essentially a repeat of the right-wing social democracy of the post-war era: an appeal to the most basic material interests of workers that avoids confrontational political issues. Obviously, socialists must fight for these basic material interests, but to address only these issues falls into the problem of what Lenin defined as economism in his work What Is To Be Done?. Lenin’s use of the term (and the way we use the term here) was in the context of a polemic with Russian Marxists who believed that socialist organizing should focus merely on trade union struggles, leaving political issues related to extra-economic oppression to liberal reformers. The economists believed that through the economic struggle alone workers would spontaneously develop a socialist consciousness even without an active political struggle from socialists. Contrary to this approach, Lenin argued that “the Social-Democrats ideal should not be the trade union secretary, but the tribune of the people, who is able to react to every manifestation of tyranny and oppression, no matter where it appears, no matter what stratum or class of the people it affects.”10 Most reactions to the rise of popular identity politics is essentially a form of economism which argues that we must focus on economic issues and base our politics on these issues alone.

Economism is essentially incapable of leading to something beyond the capitalist system on its own. Fights for expanding welfare services, higher wages, and better working conditions are an essential basis for class struggle. However, such struggles are spontaneously generated by the dynamics of capitalism itself, as capitalism is a dynamic system that can adjust to new demands placed on it. If we seek to fight for a new political order it is necessary to move beyond these spontaneous struggles and instead point to the need for a new political order, to make the economic struggle into a political struggle. To avoid any kind of divisive political issues by focusing solely on basic economic demands, one easily falls into the logic of social chauvinism, where the movement avoids taking any kind of position controversial to the capitalist order in the name of maintaining as large of a constituency as possible. In the face of political issues such as imperialism, racism, and gender oppression, this strategy results in the movement acquiescing to the path of least resistance due to fear of entering into contradiction with the masses.

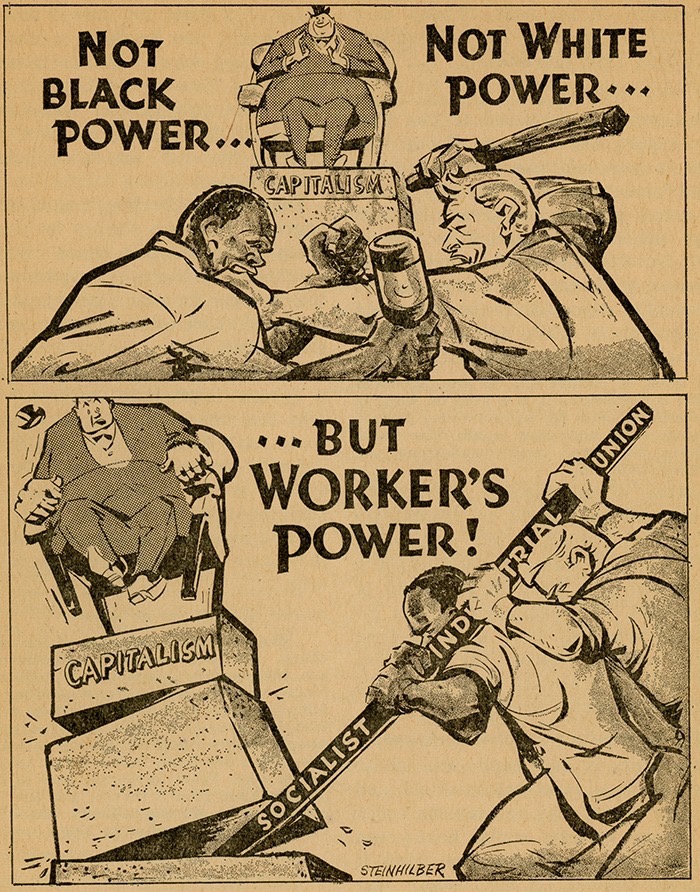

Such logic has led to infamous results, such as the German SPD’s support for World War One, the AFL in the United States supporting Chinese Exclusion laws, or striking workers demanding the exclusion of women from employment to reduce unemployment in the Great Depression. It is a logic born of a narrow-minded focus on securing a constituency and achieving maximum economic benefit within the overall logic of capitalism. One can argue that the New Left, and later intersectional identity politics, rose as a reaction to this left social chauvinism, identifying a focus on class as the cause of these betrayals. But in the face of the left fracturing into a variety of identity groups that can only unite based on coalitions, the logic of focusing on economic issues has a certain appeal. It is through economic struggles that various identity groups can unite across cultural differences into a common project. What the economists get wrong is that they see class not as a means of uniting humanity into a common project for humanity, but rather as a category that (like identity groups) must bargain for the best possible position in the existing framework of our society.

It is important for us to remember why Marx and Engels saw the working class as a revolutionary class. It was not only because of their ability to collectively withdraw their labor power in strikes in order to put demands on their employers. Rather, it was that the proletariat, defined as those dependent on the general wage fund paid out by capitalists, could only secure emancipation by uniting as an entire class across various sectional divisions and collectively replacing private appropriation of the means of production with their democratic management of society. Through its collective existence as a class, the proletariat carries within itself the key to human emancipation. As Mike Macnair eloquently puts it,

“It is not the employed workers’ strength at the point of production which animated Marx and Engels’ belief that the key to communism is the struggle for the emancipation of the proletariat and vice versa. On the contrary, it is the proletariat’s separation from the means of production, the impossibility of restoring small-scale family production, and the proletariat’s consequent need for collective, voluntary organisation, which led them to suppose that the proletariat is a potential ‘universal class’, that its struggles are capable of leading to socialism and to a truly human society.”11

For Marx, the working class was not simply an oppressed group that was disadvantaged by unjust laws or discriminated against but a section of society whose emancipation included “that of all human beings without distinction of sex or race.”12 Marx’s focus on class was not meant to sideline issues of national oppression or gender oppression but to serve as an axis to unite across various groups in a greater social project — universal emancipation. Contrary to Crenshaw’s intersectionality, class is a category that has an essential role in socialist politics beyond that of other identity groups, and contrary to the ideology of economism, the proletariat’s liberation is not simply the liberation of the working class but the destruction of “all the inhuman conditions of life in contemporary society.”13

This is not to dismiss or sideline political claims based on identity. To do so out of fear of divisiveness creates the aforementioned danger of falling into social chauvinism. We cannot allow for class-blind politics any more than we can have color-blind politics. Race and gender oppression have a cross-class basis, i.e it is not only Black proletarians who experience racism. Identity groups, therefore, have a common experience of extra-class oppression and therefore can unite around this experience of oppression. But within these identity groups class divisions exist which influences individuals’ experience of oppression and strategies for fighting back against it. This is where the most important aspects of Reed’s critique factor in. The elites within identity groups tend towards a politics of “brokerage”, trying to navigate within the system to assure a solution to political problems while maintaining their class positions. As a result, identity politics can result in movements that primarily serve the bourgeoisie while leaving the proletariat behind. This is best exemplified by movements that tend to focus purely on upward mobility for oppressed groups.

For Marxists, the answer to this issue shouldn’t be to ignore the struggles of oppressed groups in favor of a purist conception of economic struggle but to reveal the class antagonisms within identity groups and fight for the leadership of the proletariat within these struggles. To paraphrase Lenin as quoted earlier, we must not be mere “trade union secretaries” but “tribunes of the people” who “react to every manifestation of oppression.” In fact, when class struggles interact with democratic and extra-economic political struggles it can point in a revolutionary direction beyond bargaining within the existing system. As Louis Althusser points out in Contradiction and Overdetermination, the Russian Revolution was not a product of the mere contradiction between labor and capital, but a result of an accumulation of contradictions relating to the struggles of oppressed nationalities, peasant demands for land reform, and imperialist war, allowing the class struggle to manifest itself in a way that pointed beyond its limits.14

In the United States, where the legacy of racism is very much intact, we leave the struggles of oppressed groups under the leadership of bourgeois and managerial elites at our own peril. In his analysis of the weakness of the US labor movement and the rise of reactionary politics in the US, Mike Davis argues that “the failure of the postwar labor movement to form an organic bloc with Black liberation, to organize the South or to defeat the Southern reaction in the Democratic Party, have determined, more than any other factors, the ultimate decline of American trade unionism and the rightward reconstruction of the political economy during the 1970s.”15 Failing to fuse the democratic struggles of oppressed minorities with the class struggle will only lead to toothless politics. It is no surprise that the Communist Party USA was most successful when it militantly fought for the rights of Black Americans.

We must also understand that identity politics are not a conspiracy of the ruling class aiming to defang class consciousness, but an ideology that arises from the real experiences of oppression in a heartless world. We live in an atomized and individualistic culture. Therefore, people will often by default navigate the issues in an individualistic way. In a world that is already brutal and cruel, we risk marginalizing ourselves from the oppressed by critiquing these politics in cruel and demeaning ways. There are, of course, bad faith opportunists and careerists who wish to manipulate identity issues, but the truth is that many people come into politics through online communities that most directly speak to their issues. Knee-jerk dismissal of all politics based on identity without understanding the very real conditions that lead to these politics will only marginalize people we aim to reach. It is not a mystery why people organize as identity groups in response to issues they face — for example, Black people organizing as Black people against racialized police violence is completely rational. We do ourselves no favors by telling them to put down their struggles, yet we also do ourselves no favors by refusing to critique the bourgeois elites who aim to profit off these struggles. What is necessary is a universalist class politics that can engage all terrains of social life, is capable of developing and practicing a critique of our entire society, and can unite the proletariat in all its diversity — to use Asad Haider’s term, an insurgent universality.16 Both identity politics and economism seek to bargain for a better position within the existing world, but communists do not wish to bargain, we wish to upend the existing order and replace it with something far better

- Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics, pgs.138-139

- Ibid, 153-154.

- Discussed by Mike Macnair here: https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1206/intersectionality-is-a-dead-end/

- Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color, pg 2

- Mark Fischer, Exiting the Vampire Castle, available here: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/exiting-vampire-castle/

- Adolph Reed Jr., Fron Jenner to Dolezal: One Trans Good, the Other Not So Much, available here: https://www.commondreams.org/views/2015/06/15/jenner-dolezal-one-trans-good-other-not-so-much

- Adolph Reed Jr., Antiracism: A Neoliberal Alternative to a Left, available here: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10624-017-9476-3

- Adolph Reed Jr., The Case Against Reparations, available here: https://nonsite.org/editorial/the-case-against-reparations

- Available here: https://platypus1917.org/2015/04/22/what-is-political-party-for-the-left/

- Lenin, What Is To Be Done, available here: https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/iii.htm

- Mike Macnair, Revolutionary Strategy, pg. 25

- Karl Marx and Jules Guesde, Programme of the Parti Ouvrier, available here: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/05/parti-ouvrier.htm

- Marx, The Holy Family, available herehttps://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/holy-family/ch04.htm

- Althusser, Contradiction and Overdetermination, available here: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1962/overdetermination.htm

- Mike Davis, Prisoners of the American Dream, pg 322.

- Asad Haider, Mistaken Identity, pg. 114

38 Replies to “Neither Intersectionality nor Economism: For a Genuine Class Politics”

Comments are closed.